The phrase “Existentialism and Chinese Literati Art” evokes a seemingly impossible collision – one rooted in 19th-20th century European angst, the other in millennia of Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian refinement. To seek a direct lineage would be a profound misunderstanding. Yet, within the **metaphysical crucible** – that intense, transformative space where fundamental questions of existence are forged – a profound resonance *does* emerge. It is not a borrowing, but a convergence of *approaches* to confronting the human condition in a universe that offers no preordained meaning, where the artist becomes the crucible itself. Chinese literati art, far from being a passive aesthetic, is a dynamic, embodied *practice* of existence, revealing an ancient, non-Western path to the existential confrontation.

Existentialism, in its core, grapples with *absurdity*: the human need for meaning in a silent, indifferent cosmos. Sartre declared “existence precedes essence,” meaning we are thrown into being *without* a predetermined purpose, and must *create* our essence through radical, authentic choices. Camus saw the absurd as the conflict between the human craving for meaning and the universe’s silence, demanding rebellion through passionate engagement. This is not despair, but the *imperative* to act, to define oneself *in* the void.

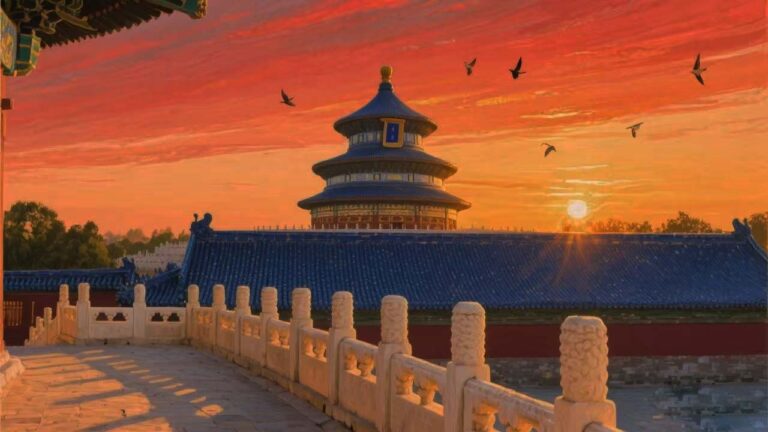

Chinese literati art, practiced by scholar-officials (wenren) from the Tang through Qing dynasties, operates within a similar, though culturally distinct, metaphysical void. The Daoist *Wu* (nothingness, emptiness), the Buddhist concept of *Śūnyatā* (emptiness, interdependence), and the Confucian focus on *self-cultivation* within a seemingly chaotic world provided the framework. **The crucible is not the cosmos itself, but the *act of creation* and *perception* within the literati’s own mind and brush.** The literatus did not seek meaning *in* the universe; he sought to *become* the meaning *through* his engagement with it, particularly through the medium of art.

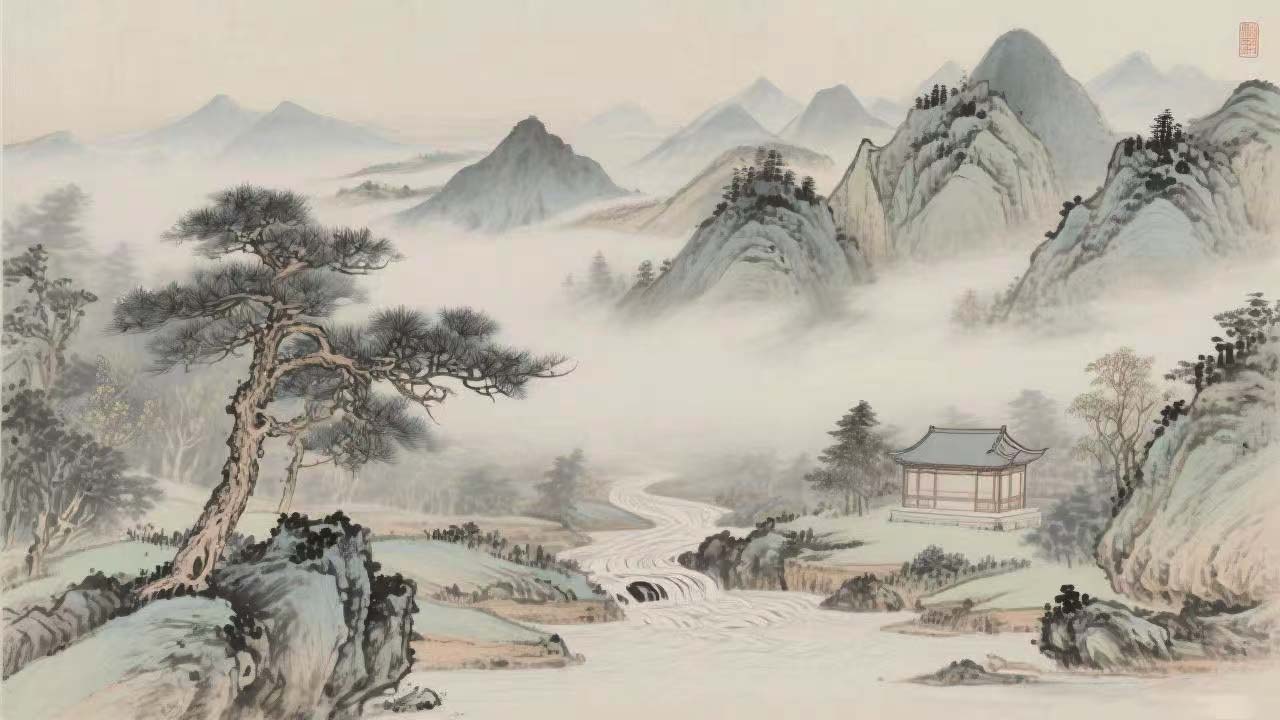

Consider the iconic literati painting: a solitary pine on a mist-shrouded mountain, a few brushstrokes suggesting a mountain peak, empty space dominating the canvas. This is not mere representation. It embodies the existential *void* – the silent cosmos – but the *act of painting* is the defiant, authentic *creation* of meaning. The brushstroke *is* the being-in-the-world. As the Tang poet and painter Wang Wei (701-761) expressed in his verse, “The mountain is empty, the forest is silent; only the sound of the stream can be heard.” The emptiness *is* the presence; the silence *is* the sound of existence. The artist does not *describe* the void; he *dwells within it* through the act of painting, making the void *his* reality, his point of being. This is the literati equivalent of Sartre’s “being-for-itself” – not a negation, but a *creative engagement* with the nothingness.

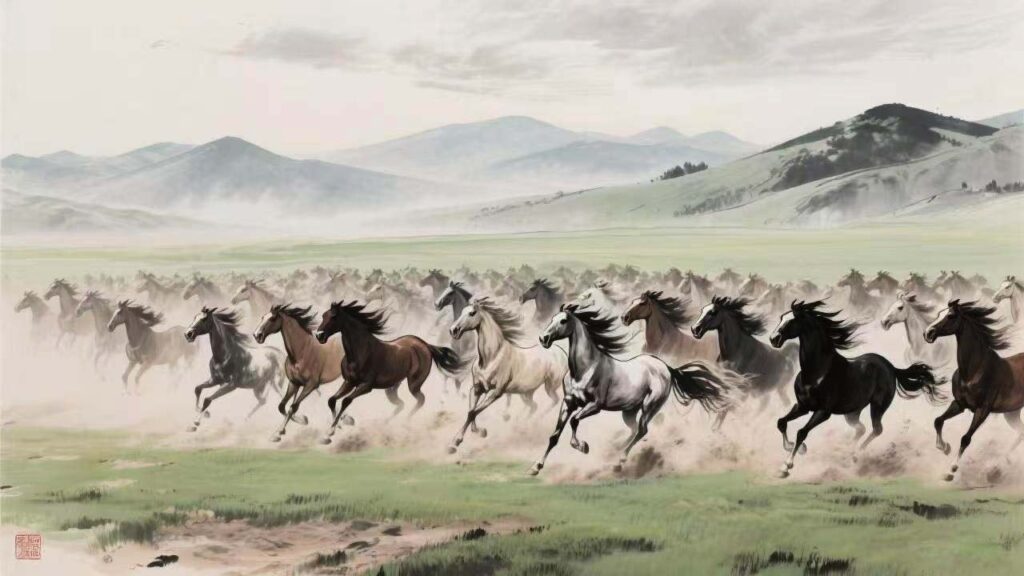

The literati’s self-cultivation (*xiu shen*) was the ultimate existential practice. It was not about achieving a fixed state of enlightenment (though that was the goal), but about *ongoing, mindful engagement* with the present moment, the natural world, and the act of creation itself. Reading, writing poetry, composing music, painting – these were not hobbies, but *essential practices of being*. In the famous story of the Zen monk who, when asked about the path, simply picked up a stone and placed it on the ground, the meaning *was* the action, not a verbalized doctrine. The literatus, in the quiet study or the mountain retreat, *lived* the absurdity – the universe offered no fixed meaning – and *chose* to find it *in the brush, the ink, the mountain’s form, the poem’s rhythm*. This is the existential *authenticity*: choosing to engage meaningfully with the void *as it is*, not through false comforts or imposed dogma.

The crucible is further illuminated by the literati’s relationship with nature. For the existentialist, nature is often the indifferent, absurd backdrop. For the literatus, nature *is* the metaphysical ground, the very expression of the Dao. The “empty” landscape isn’t empty; it’s pregnant with potential meaning *only when perceived and rendered by the artist*. The mountain *becomes* meaningful *through* the literatus’s brush. This mirrors the existentialist idea that meaning is *not* found, but *created* through our interaction with the world. The literatus didn’t ask “What is the meaning of the mountain?” He *was* the mountain in his perception and creation. The act of painting *is* the meaning, the authentic being.

To equate this directly with existentialism is reductive. The literatus operated within a framework of *harmony* (Dao) and *interdependence* (Buddhism), not the *angst* and *radical freedom* often emphasized in the West. His “authenticity” was found in aligning with the Dao, not in the radical, often isolating, self-creation of the Western existentialist. The crucible for the literatus was *within* the natural and cosmic order he sought to understand and embody; for the existentialist, it was often *against* a perceived cosmic indifference.

**Therefore, the true significance lies not in a historical link, but in a profound *methodological resonance*.** Both traditions confront the fundamental human predicament: the universe offers no inherent meaning. The Western existentialist responds with radical, often defiant *choice* and *action* in the face of the absurd. The Chinese literatus responds with *embodied practice* – the mindful, harmonious engagement with the natural world and the creative act itself – within a framework that sees meaning *arising from* that engagement, not imposed upon it. The literati’s brushstroke, the poem’s final line, the quiet contemplation of a rock – these are the *actions* that constitute existence in the void. The “metaphysical crucible” is not a place of despair, but the *very space of creation* where the literatus, like the existentialist, finds the meaning he *must* create: *in the act of being, perceiving, and making*.

The literati art of China, therefore, is not a mere aesthetic tradition. It is a **living, non-Western existential practice**. It offers a powerful counterpoint to the Western narrative, demonstrating that the confrontation with meaninglessness and the imperative to create meaning can be expressed through a path of harmony, mindfulness, and the sacredness of the present act – not through the lens of angst, but through the lens of *being*. In the quiet studio, with brush in hand and mountain in the mind, the literatus forged his essence not in defiance of the void, but *within* its embrace, proving that the most profound existential act is often the most unassuming one: the act of *seeing* and *making*, right here, right now, in the metaphysical crucible of existence itself. The void is not empty; it is the canvas, and the brush is the self.