Li Wei had been taking the same subway line for the past ten years. The trains hissed past the neon‑lit boards, the air was a mix of diesel and incense, and every morning he stepped out of the same 17‑storey apartment in Chaoyang, took the same lift, and walked the same corridor into the glass façade of the Future Tech headquarters. His job was to debug lines of code that would eventually power smart assistants for millions of people. When he returned home, the soft hum of the city faded into the quiet thrum of his apartment, the only sound his brush sliding across a canvas.

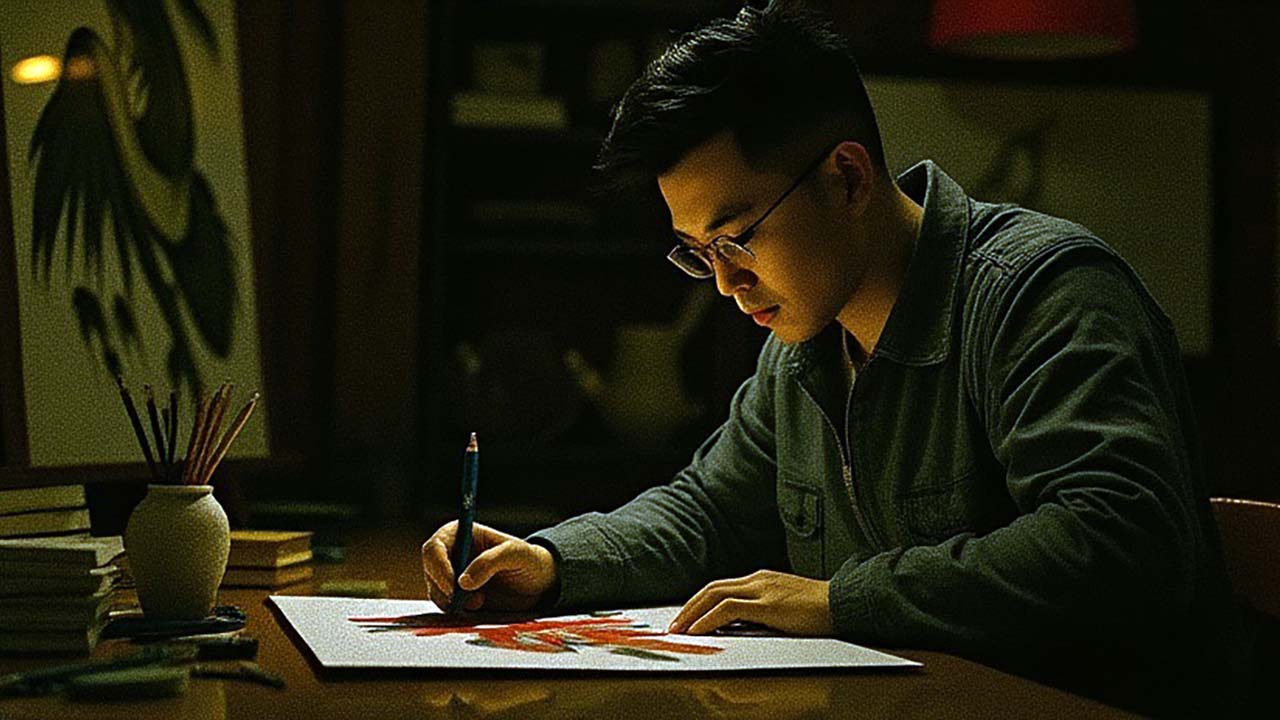

He had a small easel set up on the balcony, where the view of the city looked like a watercolor from above. Every night, after a long day of meetings and meetings, Li Wei would pour a cup of jasmine tea and let his fingers find the rhythm of charcoal on paper. He was a quiet man, someone who liked the way a blank page could feel like a promise.

On a Friday afternoon, after a particularly brutal client presentation, Li Wei walked past the ancient hutongs that still clung to the heart of Dongcheng. A wooden sign caught his eye: “Hutong Community Arts Studio.” Curiosity nudged him inside. The studio smelled of linseed oil, old paper, and the faint fragrance of plum blossoms from a pot on the windowsill. At the center, a thin‑set table bore a stack of canvases, each covered in a blur of colors that only the eyes of an expert could appreciate.

A man around sixty, with a thin beard and a head full of silver, looked up from a sketchbook. “You must be new here,” he said in Mandarin, his voice steady, “I’m Wang, the instructor.”

Li Wei nodded. “I’m Li Wei. I work at Future Tech. I paint on the side.”

Wang smiled. “Painting on the side is a good way to keep the mind relax. But have you ever tried to paint something you haven’t seen?”

Li Wei blinked. “What do you mean?”

Wang gestured to the canvases around them. “This is not just about what you see with your eyes. It’s about what you see with your mind. We call it “remote viewing”, not in the sense of seeing distant lands, but in the sense of seeing places beyond the reach of your eyes, the essence of a place that isn’t physically present.”

Li Wei leaned in. “How do I do that?”

Wang closed his eyes. “Take a breath. Picture a place. Not a place you’ve walked, but a place that feels like a story. Let it unfold in your mind. When it settles, start to paint. The brush will follow the rhythm of your thoughts.”

Li Wei was skeptical, but the idea of unlocking a hidden part of himself was intoxicating. He had always felt a tug toward something larger than his daily routines. After the studio closed, he returned to his apartment with Wang’s words echoing in his mind.

That night, he closed his eyes and thought of a place he had only visited once, a rocky outcrop on the outskirts of the Great Wall, where the wind sang like a violin and the sky was a deep indigo. He felt the cold stone under his fingertips, heard the distant echo of a drum, smelled the faint scent of pine. The image was vivid, though he’d never been there for more than an hour.

He opened his eyes, picked up a charcoal stick, and let the tip glide across the paper. Lines emerged like a map, the rock formations rising from the ground, the wind-blown grasses swirling around a lone pine. The brush seemed to move on its own, following the rhythm of his inner sight. When he finished, the canvas was a living landscape he could hardly have imagined from any memory.

The pther day, Li Wei shared his work to Wang. “You have it,” he said softly. “You didn’t just paint what you saw; you painted what you felt. That’s the first step of remote viewing with art.”

Li Wei felt a strange mixture of disbelief and wonder. His mind had always been a reservoir of memories and thoughts, but never had it seemed to have a compass that could point toward unseen places. That night, as he stared at his painting, he realized that his eyes were merely one portal; the mind was a vast ocean that could reveal hidden horizons.

Over the next few weeks, Li Wei returned to the studio, practicing the technique under Wang’s guidance. He found that the more he relaxed, the clearer the images became. He painted not only remote landscapes but also the subtle emotions of people, a mother’s tenderness in a bustling market, a soldier’s resolve in a quiet fortress. The paintings grew richer, more nuanced. The local artists began to take notice. A small gallery in the nearby invited him to showcase his work.

One day, while perusing an old catalogue of Qing dynasty paintings, Li Wei stumbled upon a faded portrait of a woman who ad beenh a renowned calligrapher in the 18th century. The catalogue mentioned that the original painting was rumored to be hidden in a forgotten hutong, behind an old tea house that had been converted into apartments. The story intrigued him. He thought of the painting, imagined the cramped space, the smell of tea, the subtle flicker of candlelight. When he drew, the brush moved with an almost instinctive grace, revealing a narrow corridor lined with ancient brick, a door slightly ajar, a shadow that seemed to beckon.

Without hesitation, Li Wei managed a weekend trip to the hutong. He walked past the bustling modernity of Beijing, and found himself in a maze of narrow lanes. He followed the clues from his painting, turning corners, listening for the faint echo of a drum. Finally, he found the old tea house, its façade a faded testament to a time long past. Behind a false wall, concealed beneath layers of wallpaper, he discovered a small wooden box. Inside, wrapped in delicate silk, lay the portrait. Its ink still fresh, the woman’s eyes seemingly alive.

He felt a thrill that transcended the usual satisfaction of an artist. He had used his art, his remote viewing, to uncover a piece of cultural heritage that had been lost to time. The painting was taken to the Beijing Museum of Fine Arts, where it was displayed alongside a photograph of Li Wei, brush in hand, in the same hutong that had become a conduit between past and present.

The exhibition drew crowds. Visitors marveled at the discovery, and many asked Li Wei about the process. He spoke with Wang’s wisdom: “We paint the unseen by letting our minds be a canvas. We train our eyes to listen, our hearts to feel, and our brushes to follow. The city is full of hidden stories. All it takes is the courage to look beyond the obvious.”

Li Wei’s name became a buzzword among the local art community. Yet he never abandoned his job at Future Tech. He found a new rhythm: the mornings were spent coding, the evenings in the studio. He began offering free workshops to colleagues, teaching them the basics of remote viewing with art. His employees, initially skeptical, found themselves exploring new dimensions of creativity, even if it was just the way they saw their own lunch boxes.

Years later, Li Wei stood in front of a large canvas at a Beijing gallery, his brush poised. He had painted a scene of the Forbidden City at sunrise, but instead of a faithful reproduction, it was a look of light and shadow that captured the aura of the palace. A young girl in the audience whispered, “I can feel the cool stone in my hands.” Li Wei smiled. The brush had indeed become a magic wand to the unseen, a reminder that the world holds more than what meets the eye.

In the quiet of his balcony, after the city’s lights had dimmed, Li Wei reflected on the path that had led him from a routine office life to an unexpected calling. He realized that the real remote viewing wasn’t about seeing far away; it was about seeing deeply. The unseen parts of places, of people, of his own heart. Those were the landscapes he could still explore. His brush was no longer a tool for a hobby; it was a key that unlocked hidden realms, a bridge that connected the tangible to the intangible, and a reminder that even in the bustling metropolis of Beijing, there were hidden stories waiting to be painted. When a new generation of art students began to gather around his workshop, Li Wei felt a quiet pride. He had shown them that the world is full of unseen wonders, and that with a little practice, one could paint them. The city, with its neon glow and ancient stones, had become his canvas, and the stories he uncovered were a testament to the power of seeing with the mind. The brush of the unseen, he whispered to himself, was a gift that he intended to share, forever inspiring others to look beyond the surface.

(LKW Original)