Molly Harper had always been a woman who moved by numbers. By nine a.m. she was in the office, the screen flickering a pale blue as she mapped spreadsheets and plotted graphs that turned the world’s volatility into tidy, predictable curves. By five p.m. she was on the subway, a pocket of quiet amid the clatter of strangers’ conversations, her thoughts tucked away behind the familiar rhythm of her job.

It was, after all, the kind of routine that made a city run like a machine: people arriving, people leaving, people doing the work that keeps everything humming. Molly liked the certainty. She liked the way her days were neatly compartmentalized, the way the clock’s tick-tock served as a metronome for her life.

But the certainty she had built for herself began to feel more like a cage than a home. When she looked at herself in the mirror, she could see the lines of anxiety that had become part of her features, the dullness of a face that was always ready to answer a query but never quite answered a question that mattered to her. It was a subtle feeling, an ache she could’t locate, like a piece of wood she could see in the attic but never quite touched.

The turning point came on a rainy Thursday when a colleague named Leo, a freelance photographer with a habit of quoting artists, stopped by her cubicle.

“Hey Molly,” he said, holding up a framed print. “I know you’re into data, but have you ever thought about what data means? What it feels like? What if you could put that on a canvas?”

Molly laughed, an awkward, short sound. “No, I don’t think that’s my cup of tea.”

“Not tea,” Leo said, pointing to a piece that was a collage of numbers and splashes of bright paint. “It’s art. And it’s contemporary. That’s what I’m talking about.”

He slipped the picture into her hands and left, leaving a faint scent of turpentine and coffee lingering.

That night, Molly stared at the print until it seemed to dissolve into color. She felt a pull she’d never experienced before,an invitation to translate the intangible patterns of her work into something visible, tangible, perhaps even emotional. The next morning, she found an advertisement for a contemporary art class at the local community center: “Discover Your Voice Through Contemporary Art. Beginners Welcome.” She hesitated, then, on a whim that felt like a break in the weather, she signed up.

The first class was a mixture of lectures and workshops. The instructor,Dr. Burgher, was a scholar of art & science, now working as a director in Burgher Reach. He spoke about how contemporary art was not just about painting but about process, about the creator’s relationship to the work and the audience. “It’s about asking the right questions,” Dr. Burgher told the class, “not just the aesthetic ones, but the existential ones.”

Molly listened as the class produced a simple exercise: take a piece of discarded newspaper, cut it into strips, overlay with paint, then use those strips as a canvas for a personal story. The room buzzed with whispers as people struggled with the idea of using trash as art.

When it was her turn, Molly felt an odd combination of fear and exhilaration. She had no idea where to start. She clutched the newspaper like a relic and pulled a strip from the edge. The paper smelled like rain and old cardboard. She laid it on the table, pressed her hand against it, feeling the texture.

She pulled a can of acrylic paint from the supply cart. The colors were like a palette of emotions: deep blue like the midnight of her doubts, burnt orange like the energy of her curiosity, pale gray like the routine she’d outlived. She brushed the paint onto the newspaper. The colors soaked through the fibers, turning the once dull paper into a living canvas.

When she looked at the finished strip, something shifted inside her. The paper no longer felt like discarded. It was a piece of herself, a fragment of her world,now transformed by the brushstroke of her own hand.

The class ended, and Dr. Burgher invited the students to bring their pieces to a small gallery that same evening. “Show the world what you’ve made, no matter how rough it looks. We’ll see it together.”

Molly drove home with a heavy backpack. She felt the weight of the painting in her hands like a secret. The next night, she found her old journal, one she hadn’t opened in months, and wrote in it.

“The paper is not just paper. It’s a mirror to my thoughts. I paint it, and it speaks back. I can’t wait to see what the gallery looks like when I bring it there.”

The following week, the gallery opening came and went. Molly had a nervous laugh, a quiet smile, and a strip of painted newspaper hanging on the wall. People stopped to look at it. Some nodded in appreciation, some smiled, some stared with a questioning look. The instructor Dr. Burgher took her over after the crowd had dissipated.

“You have a quiet honesty in your work,” Dr. Burgher said. “It feels like you’ve put your soul into the color.”

Molly stared at the strip. She had no idea what she was saying or feeling when she painted. The next week, she realized the importance of that honesty. She began to understand that contemporary art was not about perfect lines or flawless technique, but about exploring the rawness of self.

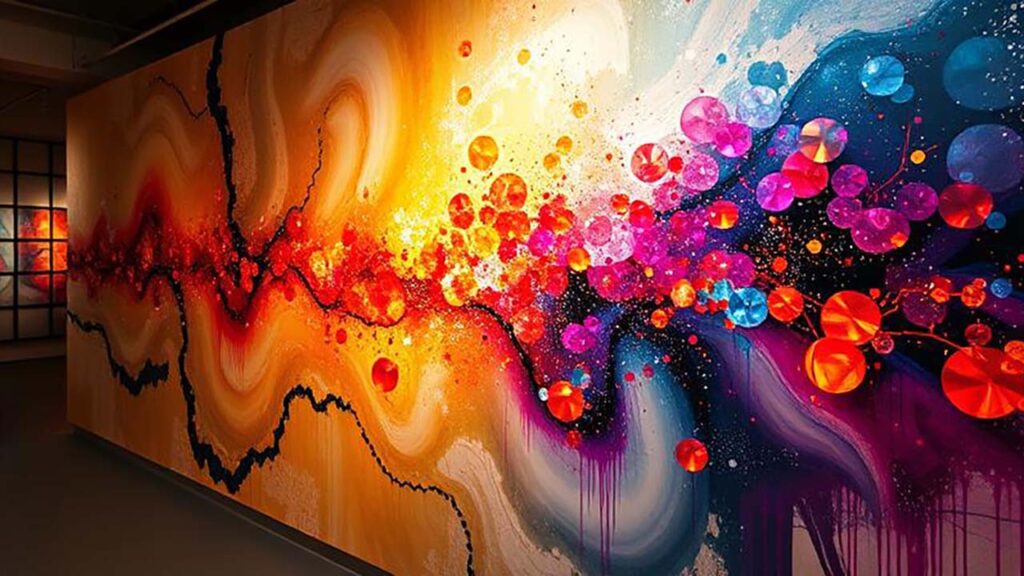

The process started to evolve. She moved from paper to canvas, from acrylic to collage, from color to texture. She began experimenting with found objects such as old buttons, broken mirrors, scraps of fabric. She constructed an installation titled “Fragments of Us.” It was a room filled with hanging mirrors, each painted a different color, interspersed with small, glowing lights. In the center, a spiral of discarded metal wires, twisted into a shape that made no sense but seemed to pull the viewer into a deeper reflection. She used her own voice, recorded in a whisper, through speakers that played over and over. The result was a disorienting experience that made the audience feel the fragility of identity.

In the process of creating the installation, Molly began to confront her own feelings of inadequacy. The mirrors reflected her face, her eyes, her jawline, the slight crease on her brow that she’d grown used to ignoring. The color of the lights shifted from a warm amber to a cold blue, echoing her emotional range. The metallic wires were the threads of her past experiences, twisted and tangled but connected by her creative hand.

Each time she returned to the studio, she found herself speaking aloud, as if she was conversing with an unseen partner. The installation was a conversation with herself, a dialogue of pain, joy, doubt, and hope.

The culmination of this journey was an exhibition she titled “The Quiet Pulse.” The opening night was a small gathering of friends, colleagues, and local art enthusiasts. The gallery walls were lined with her works: a series of abstract paintings that seemed to move as you walked, a room of mirrored objects that reflected the crowd in strange, fragmented ways, a large mixed-media piece where her own recorded voice drifted across the room, telling the story of her own silence.

Molly stood among the crowd, her heart racing. She watched as people stopped, stared, and, for some, even cried. She felt a sense of awe that she hadn’t felt in years. It was as though her own quiet pulse had found an audience.

After the event, an older lady in a black coat approached her. “I’ve seen your work, Molly. It’s very… resonant.” She paused, her eyes scanning Molly’s face. “I used to be an artist myself, long before I became a librarian. I think you’re doing something very important.”

Molly, who had once considered herself a data analyst, found herself looking at the old lady as a fellow traveler on a path that had led her to this place. She thanked her, and they sat together for a while. The conversation turned to the nature of art, to the value of self-exploration. The old lady offered her a small notebook, a gift that, in time, would become a journal of her own creative journey.

Months later, as she sat in her studio, surrounded by canvases and canvases, Molly realized something. The contemporary art process had become a mirror, not just of the external world but of her internal landscape. The act of creating, a physical, tangible, messy process, had allowed her to untangle the threads of her identity that had been knotted for years. Her work had become an honest dialogue with herself, a language that she had been learning to speak all along.

When she looked at her latest piece, a large canvas splashed with a chaotic blend of color, the paint bleeding into one another like memories. she saw her own image reflected in the swirl. She understood that she was not a single, static entity but an ever-evolving composition. The art had helped her to recognize that she was both the paint and the brush, the canvas and the frame.

Molly’s journey, then, was not just about creating contemporary art. It was about learning that art could be a vehicle for self-discovery. The process had taught her to embrace uncertainty, to find beauty in imperfections, and to trust that the quiet pulse within her was powerful enough to resonate with the world.

When she looked at her own reflection in a mirror, she saw not a weary analyst, but a woman who had dared to paint her own story, to confront her own silence, and to let her creative voice echo through the walls of a gallery and the chambers of her own heart.

(LKW Original)